Wood Destroying Organisms

Treatments, and Products

Most problems in Washington caused by carpenter ants are due to Camponotus modoc and Camponotus vicinus. These species commonly nest in standing trees (living or dead), in stumps, or in logs and branch off into nearby structures forming satellite colonies/nests.

About Carpenter Ants

BIOLOGY AND CONTROL1

Structural Damage

Carpenter ants are a problem to humans because of their habit of nesting in houses (Fig. 1, 2). They do not eat wood, but they remove quantities of it to expand their nesting facilities. This can result in damage to buildings and, if the main structural beams are hollowed out, can result in an unsafe condition. Typical damage is shown in Fig. 3.

Most carpenter ant species establish their initial nest in decayed wood, but, once established, the ants expand their tunneling into sound wood and can do considerable damage to a structure. However, this damage occurs over 2 or more years, since the initial colony consists of a single queen. Workers are produced at a slow rate, so that a colony consisting of 200 to 300 workers is at least 2 to 4 years old.

Most problems in Washington caused by carpenter ants are due to Camponotus modoc and Camponotus vicinus. These species commonly nest in standing trees (living or dead), in stumps, or in logs and branch off into nearby structures forming satellite colonies/nests.

A number of workers from these large “parent” colonies will frequently move into a dwelling as a “satellite” colony. Communication and travel between colonies is maintained, and the satellite colony may contain larvae, pupae, and winged reproductives. Since these colonies are already established, damage to houses can occur in a shorter time and is not limited to decayed wood. Indeed, these ants may become established in houses still under construction. The size of a typical colony is probably 10 to 20,000 workers, and large colonies can have up to 100,000 workers. Not surprisingly, satellite colonies found in houses frequently contain up to several thousand workers.

The ants usually maintain a trail between the parent and satellite colonies. These trails follow natural contours and lines of least resistance and frequently cut across lawns. The trails are about 2 cm wide, and the ants keep them clear of vegetation and debris. Traffic on these trails may be noticeable during the day, but peak traffic occurs after sunset and continues throughout the night, sharply decreasing before sunrise.

The parent colony is often located in a tree, stump, or in stacked wood within 100 meters of the house. Wood and stumps buried in the yard when the house was constructed or stumps and decorative wood pieces used to enhance the beauty of a yard or driveway may also be the source of a parent colony.

Identification

Carpenter ants, genus Camponotus, belong to the sub-family Formicinae, which is characterized by a circular anal orifice surrounded by a fringe of hair. Carpenter ants are large, having queens about 16-18 m long. (Fig. 7A) and workers varying from 6-13 mm long (Fig. 7B. and C). When workers vary in size, they exhibit polymorphism (many sizes). The workers of some ants are monomorphic (one size).

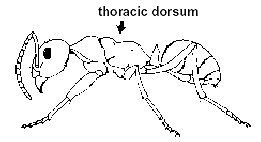

For species identification of carpenter ants, you must collect the largest workers, called majors. Camponotus workers are easily recognized by the thoracic dorsum, which is evenly convex when viewed from the side (Fig. 8) Other ants that may be confused with Camponotus have a notch or depression on the thoracic dorsum (Fig. 9). Color is not a good means of identification, as Washington has several species of carpenter ants that vary in color from all black to red thorax with black gaster (the enlarged part of the abdomen) and head, to a light brown. However, the most common Camponotusinfesting houses and other structures in Washington is Camponotus modoc. This species is black except for the legs, which are reddish.

Life History

All ants undergo complex metamorphosis, or change, and pass through the following stages: egg, larvae, pupa, adult. Under normal conditions, the egg to adult sequence takes about 60 days. Nests contain workers (sterile females), and single functional queen (usually), and may also contain winged queens and males (Fig. 7D), which are produced during the late summer and overwinter in the nest.

During the first warm days of spring (January-June, depending on locality) these reproductives emerge from the nest for their mating flights. After mating the males die. The inseminated queen selects a nest site, usually in a small cavity in a stump, log, under bark, or in the timbers of houses. The queen then breaks off her wings along lines of predetermined weakness, and within a few days lays her first eggs. These soon hatch into larvae, which are fed by the queen from reserves within her body. The queen does not leave the nest to forage for food during the entire time she feeds and raises this brood.

At the end of their developmental period, the larvae pupate and eventually emerge as workers. Since these first workers have been fed only on the reserves within the queen’s body, they are very small and are called minors or minor workers (Fig. 7C). They usually number about 15 to 25. These workers then take over the functions of foraging for food, nest excavation, and brood rearing.

The queen’s primary function from this point on is to lay eggs. The colony produces successive broods and, since the larvae are fed by foraging workers, the size of the workers increases; some may be very large and are called majors (Fig. 7B). The colony does not produce reproductives (winged males and queens) until it is from 6 to 10 years old and contains about 2,000 workers. Dorsal views of all adult forms are shown in Fig. 10.

While most carpenter ant colonies are probably initiated by a single queen, queens may also initiate colonies in close proximity of each other to create multiple queen colonies. These colonies are probably more successful and grow at a faster rate.

The natural food for these ants consists of insects and other arthropods and sweet exudates from aphids and other insects. They also are attracted to other sweet materials such as decaying fruits.

figure 1

figure 2

figure 3

figure 7

figure 9

figure 10

In coastal areas of Washington wood-infesting beetles cause extensive damage to wooden buildings. Damage often is overlooked, as these insects live in portions of the structure where people seldom see them.

About Anobiidae Beetles

ANOBIIDAE BEETLES IN STRUCTURES 4

In coastal areas of Washington, wood-infesting beetles cause extensive damage to buildings. Damage often is overlooked, as these insects live in portions of the structure where they are seldom seen. Wood breakdown from beetle infestations can lead to serious structural weakness (Fig. 1). In addition, chemical treatments and wood replacement to limit insect damage are costly. Hemicoelus gibbicollis (LeConte), a member of the beetle family Anobiidae, causes the most significant damage. Several other anobiid species occur in wooden timbers, though they usually build to damaging levels over a period of years.

Structure-infesting anobiids occur primarily in older homes with crawl spaces or damp basements. These beetles also infest outbuildings, such as barns or garages. Wooden support timbers, floor joists, and sub-flooring are commonly infested. Larvae also feed on plywood. New replacement wood attached (or scabbed) over old infested wood is more likely to be attacked and shows damage very quickly. Whether or not odor and texture play a part, the new wood has higher nutritional value and attracts the insects. Once established, and if environmental conditions remain appropriate, anobiids will continuously reinfest until only powdery frass (feces) covered by a thin layer of wood remains (Fig. 2). Conditions of high moisture, no ventilation, and poor drainage away from the structure encourage the development of these insects. Homes in Washington west of the Cascade Mountains are most susceptible, and beetles favor those near coastal areas.

Description

People rarely see these insects. Adult beetles range from 2 to 5 mm long and are reddish to chocolate brown in color (Fig. 3). Eggs are 0.5 mm long, white, and tear-drop shaped (Fig. 4). Larvae are white, C-shaped, and 5 to 6 mm long when fully developed (Fig. 5). Pupation takes place just beneath the wood surface (Fig. 6).

Life History

Adult beetles mate during July and August and females soon lay 10 to 30 eggs singly or in groups of 2 to 10 within natural depressions of wood. Eggs hatch in about 3 weeks and newly emerged larvae bore directly into wood or, quite commonly, leave the oviposition site to find a more suitable place to feed. Anobiids may spend 4 to 5 years in the larval form feeding on wood. In late spring and early summer, mature larvae bore tunnels to within a few millimeters of the wood surface to pupate and change into adults. Adult beetles chew a circular exit hole and emerge during June, July, and August. These holes are often seen in large numbers on a wooden surface (Fig. 7)

Monitoring

Since these insects are so well hidden, it is extremely difficult to determine whether an infestation is active. Finding exit holes does not always mean anobiids still are feeding within the wood. Discovering frass as it is pushed out of exit holes is the best indicator of larval activity (Fig. 8). Remember that frass can filter out of exit holes due to normal activities in upper levels of a building. Often infestations will die out for undetermined reasons. Before undertaking control measures, have the building inspected and try to determine infestation levels. To check for new frass being expelled, place a black background under areas that are suspect for several weeks during summer months, or paint portions of wooden surfaces to look for new adult exit holes. Researchers are currently testing light traps to catch adult beetles in crawl spaces. Low levels of activity (that is, a few exit holes in one or two boards in the building) do not warrant control.

Use a hammer to tap on wood and listen for differences in sounds. If the wood does not sound solid, anobiids may be present. When a knife penetrates easily into the timber and dustlike frass appears, examine that portion of the structure further to determine if wood replacement or other treatments are necessary. Homes with damp crawl spaces or standing water from poor drainage or which have inadequate ventilation are prime candidates for active infestations.

Control

Several methods must be used together for anobiid control to work successfully.

Cultural Control – Anobiid beetles thrive best in wood when moisture content ranges between 14 and 20%. Lowering wood moisture by ventilation (vents near corners are especially important), repairing gutters, positioning vapor barriers to cover the entire crawl space floor, and replacing wood are the best ways to reduce anobiid populations. Remove scraps of lumber, such as form boards, from crawl spaces. These may contain beetle larvae. When replacing wood, take out as much infested material as possible and burn it. These insects will not re-infest a wooden surface which has been painted or varnished. Abandoned buildings harboring active infestations should be torn down when practical.

Chemical Control – Borates have been proven to be a very successful treatment method. This method is now the most common means of controlling and eliminating anobiid beetle infestations. In some cases, where infestation and damage are severe, removal and replacement of these materials is recommended prior to treatment. Professional borate applications work by wicking the excess moisture content, from the wood, thus changing and eliminating the condition where these pests thrive. In addition, a residual is left behind to dry out and kill any eggs that may be laid by emerging adult females.

Bostrichid (True Powderpost) Beetle

Anobiid (Deathwatch) Beetle

Lyctid (False Powderpost) beetle

Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)3 are an easily recognized group of social insects. The workers are wingless, all possess elbowed antennae, and all have a petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments between the thorax and the abdomen.

About Moisture Ants

Most ant colonies are started by a single, inseminated female or queen. From this, single individual colonies can grow to contain anywhere from several hundred to several thousand individuals.

Ants normally have three distinct castes; workers, queens, and males. Males are intermediate in size between queens and workers and can be recognized by ocelli (simple “eyes”) on top of the head, wings, protruding genitalia, and large eyes. The sole function of the male is to mate with the queen.

The queen is the largest member of the colony. She has wings but loses them soon after mating. However, scars where the wings were attached still remain. Queens usually also have ocelli, in addition to large eyes, and a large abdomen for egg production.

The worker, the smallest member of the colony, lacks ocelli (usually) and is never winged. Workers may be of one size (monomorphic) or may vary considerably in size (polymorphic). Large workers are usually called soldiers or majors, very small workers are minors.

Ants pass through several distinct developmental stages in the colony: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The egg is very small and varies in shape according to the species. The larvae also vary in size and shape but are usually white and are always legless. The pupal stage looks like the adult but is soft, white, and motionless. Many are enclosed in a cocoon of a brownish or whitish, paper material.

Ants produce reproductive forms usually at one time of the year (spring or fall, depending on species and colony disposition). Colony activity at the time of reproductive swarming is high, with winged males and queens and workers in a very active state. The queen and males fly from the colony, mate, and shortly after, the male dies. The inseminated queen then builds a small nest, lays a few eggs, and nurtures the developing larvae that soon hatch. When adult workers appear, they take over the function of caring for the queen, the larvae, building the nest, and bringing in food for the colony. Colonies may persist for 20 years or more.

“Moisture ant” is a collective name that includes a number of ant species in two major genera, which are superficially similar in appearance and size. Both are wood invaders. These are the yellow ants (Acanthomyops spp.) and the cornfield ants (Lasius spp.). In addition to the brief descriptions given here, they can be further distinguished by the shape of the constricted segment (petiolar node) which joins the thorax and abdomen. The cornfield ant possesses a petiolar node which when viewed in profile is narrow and sharp at the top; the node of the yellow ants is thicker and blunt at the top.

Yellow Ants (Acanthomyops spp.).

Most species are yellow to orange and 3-5 mm long. Monomorphic species with all workers of the same size. Maxillary palpi short, three-segmented. Usually found in soil or in rotting wood. Will feed on sweet materials and may be an annoyance in the house at times. Will also attend aphids (plant lice) for their sweet excretion (honeydew). Colonies will produce reproductives and swarm in spring or fall. Distributed throughout the state of Washington.

MAJOR CONCERN: These ants have been found in wood in houses and sheds, causing concern on the part of the householder. However, their presence in wood (these ants ordinarily nest only in wood in the last stages of decay) can be taken as an indication of a prior problem (the wood was obviously decayed before the ants moved in). Remedial actions should include removing all rotten wood and replacing it with sound material.

Cornfield and Other Ants (Lasius spp.)

Most pest species, yellow; can vary to a rather dark brown, 3-5 mm long. Monomorphic species with workers all of the same size. Maxillary palpi long, five segmented. Colonies are usually found in decayed logs and stumps, but some may be found in soil Feed on sweet materials, attend aphids for honeydew, and become a general annoyance factor around homes.

Reproductive swarming usually late summer to early autumn. Widely distributed genus, containing several species of pest status. Occur throughout the state of Washington.

MAJOR CONCERN: These ants have frequently been found associated with rotting wood in houses. While several species may bring moisture into the wood structure to increase damage, the colony was initially started in wood in an advanced stage of decay. They should not be considered a structural pest as the problem invariably existed before the colony was established. The obvious remedy is to remove the decayed wood and to replace it with sound material.

These ants will construct galleries from the rotting wood within which they feed. These galleries should not be confused with the more linear tube-like tunnels made by subterranean termites.

These ants are continually confused with carpenter ants. However, these are small ants; carpenter ants are usually large. A sure way to distinguish them from carpenter ants is to view them from the side and determine if the thoracic dorsum is evenly convex (smoothly rounded). All carpenter ants have this rounded thoracic dorsum. This characteristic applies only to worker ants and is not generally useful for identifying winged forms.

Control

These ants are not a primary structural pest, but they can speed the deterioration of wood. They also become a nuisance as they enter homes in search of food. If possible, determine where the ants are coming from. These ants require moisture to survive. They may be nesting in damp soil outside or under the house, beneath sidewalks, along foundations, or under debris and rocks in the yard. Or the ants may be living in damp, decaying wood. If the ants are nesting in wood, they may throw out sawdust as they enlarge their nests.

Cultural Control

Make periodic checks for wet, decaying wood or wet soil under the house. Correct problems which are creating a damp place for the ants to live (leaking gutters, plumbing, improperly caulked windows, etc.) do not allow wood members to come into contact with soil. These ants are also frequently found inhabiting form lumber the contractor buried in the soil next to the foundation. This wood should be removed. Replace any badly damaged wood.

Moisture ants are known as a secondary pest. A specific inspection/WDI Inspection is advised, as a more serious water/excessive moisture condition is present and should be identified. Treatment is recommended to stop the colony from growing and causing more damage, however repairing damaged wood, and the condition which caused it is vital to complete the extermination process and final results.

*Commercial use only

Since subterranean termites live in and obtain their moisture from the soil, damp wood is not essential for attack. This makes any wood structure a potential site for subterranean termite feeding.

About Western Subterranean Termites

Western Subterranean Termites 2

These are small termites. The winged form is approximately 3/8 inch (8-9 mm) long including the wings. They are dark brown to brownish black with brownish gray wings. The soldiers have a cream-colored head with black jaws and a grayish white body. They are approximately ¼ inch (6 mm) long. Nearly half their length is head and jaws. The “worker” caste is grayish white and about 3/16 inch (5 mm) long. They live in the soil in nests which may originate in buried stumps or logs that may be as deep as 10-20 feet (3-6m).

Since subterranean termites live in and obtain their moisture from the soil, damp wood is not essential for attack. This makes any wood structure a potential site for subterranean termite feeding. The most frequent type of infestation is in buildings constructed near or on pre-existing nests. Cement slab foundations are no deterrent since eventual frost cracks, cold joints between slab and foundation walls, and areas around plumbing provide easy entry for these termites.

Indications of subterranean termite infestation are swarming behavior, damage signs, the distinctive tapping sounds that the soldiers make when disturbed, and especially by the presence of shelter “mud” tubes. These are often found on the foundation walls or in cracks. Occasionally they may be suspended from soil to subflooring. The tubes provide protection from natural enemies. Although clearly diagnostic of subterranean termites, tubes are not always present. Fecal pellets of subterranean termites are often clumped in the galleries or incorporated into the shelter tubes and feeding areas of the wood and rarely are loosely scattered as with dampwood termites. Fecal material packed in the galleries of the wood appear to be “scaly” and offer a distinctive clue like that of subterranean termites rather than some other woodeating pest – even in the absence of this termite. Mature colonies swarm annually, while colonies from a primary pair may not produce swarms for several years. They may swarm at any time of the year, depending on climatic conditions. In eastern Washington, swarming is predominantly in the spring, while in western Washington, swarming is predominantly in the fall.

Pacific Dampwood

Subterranean Termite Tubing

Western Subterranean

4138 6th Avenue

Tacoma, WA 98406

P.O. Box 6947

Tacoma WA 98417